config.bin (forensics)

You are provided with what they say is “a configuration backup of an embedded device”, and that “it seems to be encrypted”.

Opening the file with a hex editor to look for any magic identifiers:

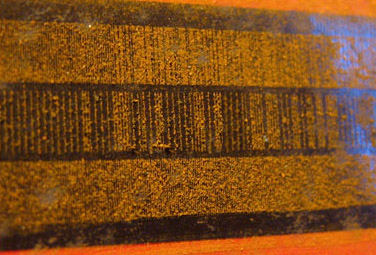

00: 4346 4731 0000 32d0 ef92 7ab0 5ab6 d80d CFG1..2...z.Z... 10: 3030 3030 3030 0000 0005 0003 0000 0000 000000.......... 20: 6261 47c3 d43b af2f 9300 bcaf adf4 5c8c baG..;./......\. 30: 3d02 9ea5 0bb7 3ce0 00f4 c5b3 901e d5fb =.....<.........

It doesn’t look familiar, so ask Google about the CFG1 file. On the second or third results page, I found this link talking about an IAD backup file in which the backup file format resembles our mystery file.

The page further notes that encryption is done through AES-256 in ECB mode, and that the 256-bit key is the ASCII string “dummy” with the rest zero-filled. There’s even a tool to decrypt it. After downloading the tool and running it, you will soon realize that the default password doesn’t work (obviously).

Fear not. This file format is pretty helpful for us though. Notice there’s a field called password_len_be, which is the length of the AES password string and plaintext_md5, which is the MD5 hash of the decrypted data. With these 2 fields (maybe just the last one), we can automate the bruteforcing.

Our file header says that a 5 character password is used (phew), but the character set is unknown. It could be all 256 characters, or hopefully just an alphanumeric string (I assumed the latter).

I wrote a multi-threaded Golang bruteforcer (which you can download here). I guess this is the time I wish I had access to a really fast machine. After an hour, it found the password:

> go run bruteforce-cfg1.go config.bin hdr hash = ef927ab05ab6d80d98c3be34a50db59c data hash = 626147c3d43baf2f9300bcafadf45c8c found password! oVX09

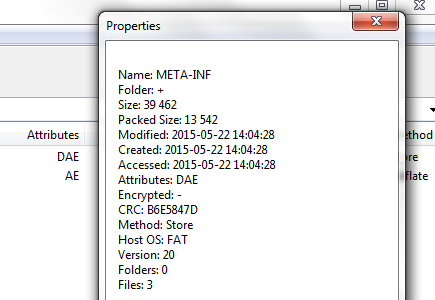

Decode it with the tool, and you will find a gzipped file config.tgz. After uncompressing it, I noticed the passwords were all short and didn’t have the regular 32C3_ prefix, until I found a suspiciously long one:

... TR069_INTERFACE="nas1.20" ACS_SERVERTYPE="default" PROVISIONING_CODE="" USERNAME="001C28-2021979797845" PASSWORD="MzJDM19jNDQ2ZWRlMjMzY2RmY2IxNzdmNGQwZTU2NzQ0NjU0Mjg5YzhkZWE0YzRlZTY1MTI2NGU4\nNWU5YWU2MmFiZjc3" CR_USERNAME="45ad2c9f00d48" CR_PASSWORD="45ad2c9f00d48" ...

Using Python for base64 decoding:

>>> from base64 import b64decode

>>> b64decode('MzJDM19jNDQ2ZWRlMjMzY2RmY2IxNzdmNGQwZTU2NzQ0NjU0Mjg5YzhkZWE0YzRlZTY1MTI2NGU4\nNWU5YWU2MmFiZjc3')

'32C3_c446ede233cdfcb177f4d0e56744654289c8dea4c4ee651264e85e9ae62abf77'

And voila!